What Are You Worth?

5 controllable inputs when working for someone else / a company

Hello, it’s Ethan & Jason. Welcome to Level Up: Your source for executive insights, high performance habits, and specific career growth actions.

Three FYIs:

Watch ‘Dissecting Amazon Leadership Principles (LPs)’. Ethan & David Anderson (Scarlet Ink) breakdown what you can learn. Watch here.

Watch ‘What a Series B Co-Founder looks for in their Leadership Team’. Jason & Dee Murthy get brutally candid. Watch here.

Read Insights from the Hiring Trenches: How Hiring Decisions are Really Made Today

I want to be paid “what I’m worth.”

You probably do, too. But how much are you worth?

Here’s the complete picture of how your pay is determined and how you can control it:

In theory, your market value is equal to the value you create. Your “fair” pay would be the value of what you produce.

If only it were that simple.

The first problem with this is “perceived” value. Maybe you have discovered a life-saving medicine, which is something that should be nearly priceless. But, if customers do not know about it or do not believe in it, then they won’t pay you anything for it.

Going in the other direction, maybe you have convinced people of the exclusive luxury of your brand, like a Ferrari. Then, people will pay you more than the value of another car because “it’s not just a car, it’s a Ferrari!”

In short, how our work is perceived changes how it is valued.

Therefore, it influences how we are paid.

This is why it is important to manage the perception of your work.

I coach many people on this issue, and most of them struggle for one of two reasons:

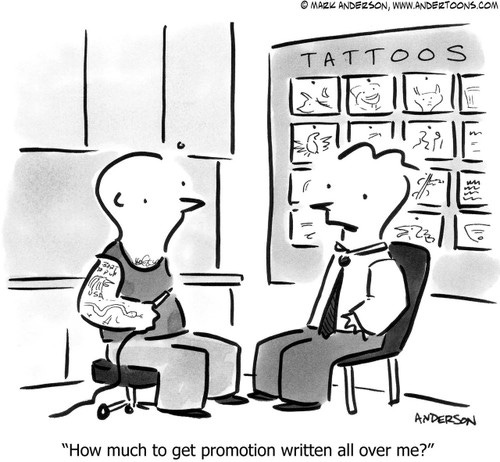

“Work hard and hope”: These people work hard and hope it will be noticed. This strategy fails because even good managers are busy and miss things. And, while you are waiting to be noticed, other people are taking steps to make sure their good work is not missed.

Fear of “self-promotion”: This issue is similar to the first, and it fails because someone else is going the extra mile to share their impact and accomplishments with decision-makers. What some may see as self-promotion, they correctly see as making sure their good work is noticed.

If either one of these reasons describes you, the simplest way to make sure your work is noticed is to send out a short, reliable status report after you complete or accomplish something, summarizing what you have done. Send it to your manager and interested stakeholders.

Below we breakdown the “allocation problem”, supply and demand, opposing incentives, irrational values, and the 5 controllable inputs when working for someone else / a company.

The “Allocation Problem”

Once your work is being noticed and perceived as valuable, the next problem people run into is the “allocation problem.”

Consider this: If I work completely alone, build an app, and sell it, it is obvious who created the value. I did. Alone. In this case, I receive all of the money from the sale.

But, let’s say I partner with a designer. I write the code, and the designer makes the app attractive and easy to use. Now, who deserves what portion of the value? Is it 50/50 because there are two of us? Or do I get 80% because I coded it? Or does the designer get 80% because it is so simple to use?

The question is complex even when it is just between two people, but now multiply this problem by the size of your team or company. If you work in a large team or company, try to identify exactly how responsible you are for generating a certain amount of revenue for the company.

Tough, right?

One way to address the allocation problem’s effect on your pay is to work for yourself or in a small company. The fewer the people, the easier it is to tie your value back to the results.

For those who work in a larger company, however, there is no easy way to allocate value accurately. This leads to the use of proxies for value (like productivity metrics), as well as to the opportunity for opinion and bias to influence your pay.

Supply and Demand

One of the most influential factors in determining your professional value is simply supply and demand. The less there is of something and the more people want it, the more it costs. The more there is of something and the less people want it, the cheaper it becomes.

Human skills follow this pattern.

For example, engineering skills are usually in shorter supply (compared to the demand) than physical labor. This is because there are fewer people who can design new software than there are who can perform manual tasks.

Calculating supply and demand is much more straightforward than trying to allocate value, so most companies figure out the market rate for a service, like your skills and your job, and then pay what they have to pay to get your skills.

This means that your pay is more directly related to what others in your field/position are being paid than it is to the value you create for the company.

So, to raise your pay, you either have to develop increasingly rare and valuable skills or convince the decision makers that you are creating more value than someone else with similar skills would. This is how you can begin to make the case that you should be paid more than other engineers, lawyers, accountants, etc.

This potential for differences in impact is where things like pay bands, promotions, and levels show up in the corporate world. For example, separating engineers into Engineers, Senior Engineers, and Principal (or Staff) Engineers is a way to systematically classify your perceived relative skills and perceived value. Pay bands are a way of acknowledging that, within some general skill level, different people will be more and less effective in applying those skills to the company’s goals.

Opposing Incentives

So, how does this all tie back to being paid “what we are worth?”